Specifically ancient funeral research from around the world. It is in my intentions that by starting this discussion we can gather here to share and learn of ancient rites and customs of various Pagan religions. If you have a favorite article you'd like to share please go ahead, just make sure it not a modern re-constructionist work. Those are also appreciated and belong in the room simply titled Funeral Rituals. Feel free to learn with us as we post our findings here gradually.

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

-

Permalink Reply by Slaying Crow O'Hagan on April 14, 2011 at 1:15

Permalink Reply by Slaying Crow O'Hagan on April 14, 2011 at 1:15 -

Burial Rituals

and the Afterlife of Ancient Greece

by Kristina Bagwell

As seen in the literature of ancient Greece, tombs and rituals of the wealthy were extravagant. Gold and jewels were essential grave offerings of respectable and honored tombs, perhaps used as a way to display wealth and status. It seems the wealthier you were the more elaborate your final resting place. The ancient Greeks had distinct methods of burial, and it was often believed if you were not provided a proper burial along with the appropriate rituals, you were destined to suffer between worlds until your rites of passage into the underworld were completed. In this essay we will see how exactly a tomb of Greece looked, the rituals followed at the time of death and also what was believed to happen if these elements were not fulfilled. Examining the tombs and rituals from the archaic period through classical Greece shows the continuity of the traditions throughout the years.

While early aristocratic Greeks built pit-like single graves in the ground or out of rock, the archaic period (600-479 BC) marks the time when tombs became more sophisticated. Now we see multiple graves in underground chambers, raised mounds, or masonry-built tombs. Archaeologists have found tombs such as these at Sindos adorned in riches of gold and jewelry (Burnstein et al. 372). The findings at the archaic cemetery are also linked to the Hellenistic period, during which the novels were written. While the sizes of the tombs of this period are larger, decorations of gold are still found throughout the tombs of the wealthy (www.museum.upenn.edu). Evidence of this extravagance is seen in a passage from Chareas and Callirhoe, “Callirhoe, as she lay there dressed in her bridal clothes, on a bier decorated with gold…” (Chariton 28).

The possessions and grave goods placed with the body did not change much; but the amounts of treasures did. The tombs of early Mycenaeans from about 1600 to 1400 BC held bronze weapons such as swords, daggers, and knives and also pottery made locally and small amounts of gold and jewelry (Burnstein et al. 21). As the years went by the grave gifts became more beautiful and plentiful. A later Mycenaean cemetery held an arsenal of weapons, and gold, silver, bronze, ivory, and alabaster gifts importe../../../../../css/d_from_places_like_Crete__Cyprus__Egypt_and_Syria__just_among_a_few._This_shows_how_much_wealthier_the_ruling_class_of_Greece_had_become__Burnstein_et_al._22.css). In Sparta, this wealth became evident around the 9th and 8th centuries BC. Before, one could hardly see a difference between the social classes (Burnstein et al. 51). Now the wealthy Greeks chose to conduct heroic-style burials in order to connect with their ancestry. Their funerals closely resemble the funeral of heroes such as Patroclus in the Iliad. The corpse was cremated and placed in a bronze urn inside a tomb that held weapons and sometimes the remains of sacrificed horses. Vases depicting heroic events reveal how the wealthy claimed descent from the heroes (Burnstein et al. 80).

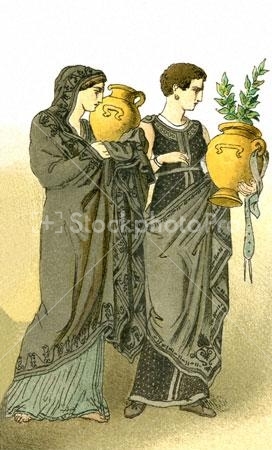

While tomb designs and grave gifts may have evolved and changed over the years, the Greeks firmly believed in a set of burial rituals. The death of Anthia in An Ephesian Tale provides evidence for these customs. “He laid her out in all her finery and surrounded her with a great quantity of gold…And there he laid her in a vault, after slaughtering a great number of victims and burning a great deal of clothing and other finery.” The family then carried out the accustomed rites (Xenophon 151). In Classical Greece the burial rituals actually consisted of three parts. First there is a prothesis, or laying out of the body. The women wash, anoint, dress, crown, cover the body and adorn it with flowers. The mouth and eyes are shut to prevent the psyche (phantom or soul) from leaving the body and the corpse is dressed in a long-ankle length garment. The body is presented so it can be viewed for two days. At the viewings, the mourners dress in black in honor of the deceased and the women stand at the head of the couch to grieve and sing while the men would stand with their palms out to the gods. When it came time for the burial, before the dawn of the third day, the body was taken to the tomb by cart. The men would lead the procession and the women would follow. At the internment the corpse or ashes would be placed in the tomb along with the grave goods of pottery, jewels, vases, or other personal property (www.perseus.tufts.edu).

White-ground lekythoi were used for funeral rites and as a gift to the deceased between 470 and 400 BC. These vases were covered with a white slip after being fired. Figures on the vase were outlined in red or black matte. The clothing of the figures pictured was colored in purple, brown, red yellow, rose, vermilion, and sky blue (www.museum.upenn.edu). Along with these gifts, offerings of fruit were made and the mourners would sing and dance. The women would leave the site first to prepare for the perideiprion or funeral party that would follow (www.perseus.tufts.edu).

Homeric belief shows that the Greeks saw death as a time when the psyche left the body to enter Hades. This psyche could be seen, but was untouchable. Beginning in Classical times there came to be the concepts of punishment after death or a state of blessedness. The soul responsible for a person’s personality and moral decisions received the eternal punishment or bliss for the choices of the human form. The burial rituals perhaps spawned from this belief that the soul must be guided into the afterlife. If the body was not given a proper burial according to Greek ritual, the soul would remain trapped between the worlds of the living and the underworld (www.museum.upenn.edu).

Demanding proper burial was one of the major reasons why ghosts would show themselves to the people of ancient Greece. Erwin Rohde, the author of Psyche: The Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality Among the Greeks, states, “The first duty that the survivors owe to their dead is to bury the body in the customary manner…Religious requirements, however, go beyond the law” (Felton 10). While most Greeks were skeptical of the belief in ghosts, there were a few who believed these suffering beings existed. Few accounts of haunting are found in Greek literature, although stories by Plautus, Pliny, and Lucian have been recovered indicating an interest in the afterlife (Felton xii).

Apuleius also provides an example of haunting by a dead spirit through dreams. In The Golden Ass, a baker is murdered, ironically, by a ghost that his wife summoned to kill him in retaliation for his request for divorce. The man is given a proper burial, yet his spirit visits his daughter through a dream to tell her what brought upon his death. “The pitiable form of her father had obtruded upon her sleep with his neck still haltered; and the dead man had disclosed to her the wicked work of her stepmother… and told her how he himself had been haunted by a spirit off the earth” (Apuleius 203). Desecrating the tombs themselves could also lead to being tormented by a spirit. Theophrastus, a 4th century author describes in “Characters” the belief that a superstitious man, “will not tread upon tombstone, for fear that association with the dead will pollute him.” One would not enter a house where a corpse laid awaiting burial either (Felton 5).

These beliefs in spirits led to great yearly festivals in Greece and Rome. The feast of Anthesteria occurred sometime in February and March in Athens. The society believed the ghosts would not leave until they were chased out. On these days everything stopped; the businesses were closed along with the temples. The doors of their houses were covered with pitch and hawthorn leaves and each family member made an offering to the dead. A meal of cooked grain was also offered to Hermes. At sunset of the last day, the master of the house would say, “Away, Spirits; Anthesteria is over” (Felton 12).

All of these rituals and beliefs of ancient Greece certainly point to the fact that Greeks were fascinated by the thought of the afterlife. What they wanted most for the dead was for their spirits to survive and be comfortable in their eternity, as seen in the grave gifts of jewels and personal property. Death was also a time for the family to show off their wealth; however, if the rituals were not followed to exactness the family might suffer the haunting of their loved one.

Works Cited

Apuleius. The Golden Ass. Trans. Jack Lindsey. Indiana UP: Bloomington, 1960.

Burnstein, et al. Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. Oxford UP: New York, 1999.

Chariton, Chareas and Callirhoe. Trans B.P. Reardon. Collected Ancient Greek Novels. U of California Press: Berkeley, 1989.

Felton, D. Haunted Greece and Rome: Ghost Stories from Classical Antiquity. U of Austin Press: Austin, 1999.

Shopkorn, Jana. “’Til Death Do Us Part: Marriage and Funeral Rites in Classical Athens.” Online. www.perseus.tufts.edu 04/09/01.

University of Pennsylvania Museum. “Ancient Greek World.” Online. www.museum.upenn.edu 04/09/01. -

-

Permalink Reply by Slaying Crow O'Hagan on April 14, 2011 at 1:16

Permalink Reply by Slaying Crow O'Hagan on April 14, 2011 at 1:16 -

Roman funeral bust

Roman funeral bust

A Roman Funeral

Throughout history, different cultures have held very different views about the concept of death and how one deals with it. As time goes on, these views continually change, as do methods for treating bodies of the deceased. During the first and second centuries AD, cremation was the most common burial practice in the Roman empire. Ultimately inhumation would replace cremation; a variety of factors, including the rise of Christianity among Romans and changes in attitudes to the afterlife, would contribute to this marked shift in popular burial practices. The objects displayed here pre-date that shift, having been recovered from a first or second century cremation burial in Puteoli (modern day Pozzuoli), the ancient harbor city of Rome.**

The Romans maintained a very systematic approach when tending to the dead. First, relatives would close the deceased's eyes while calling out the name of their dearly departed. The body was then washed and a coin was placed in the mouth. The coin was payment to Charon, who ferried the dead across the rivers of the underworld.

Social status was an important factor in the Roman funeral. The dead were put on display: the length of this ancient "wake" depended upon the departed person's position in society. Upper-class individuals, such as the nobility, were often put on display for as long as a week, offering many opportunities for many mourners to pay their final respects. Lower class members of society, on the other hand, were often cremated after only one day.

After the display, a funerary procession followed. Roman funerals were typically held at night to prevent large public gatherings and discourage crowds and excessive mourning which, in the case of major political figures, could lead to serious unrest. Hired musicians led the parade, followed by mourners and relatives who often carried portrait sculptures or wax masks of other deceased family members. The procession would end outside of town (it was forbidden to bury anyone within the city limits) and a pyre, or cremation fire, was built. As the fire burned, a eulogy was given in honor of the deceased. After the pyre was extinguished, a family member (usually the deceased's mother or wife) would gather the ashes and place them in an urn.

Many Romans belonged to funeral societies, called collegia, to ensure proper burial. They would pay monthly dues, which would be employed to cover the cost of funerals for members. Collegia members (provided they were in good standing) were guaranteed a spot in a columbarium. Columbaria were large underground vaults where peoples' cremated remains were placed within small wall niches, which were often marked by memorial plaques and portrait sculptures. Because the Romans believed that a proper burial was essential for passage to the afterlife, there was much concern on this score. Columbaria were an inexpensive way to guarantee this transition, and collegia allowed all classes of society to reach the underworld. Some emperors even provided funeral allowances to those so very poor they could not even afford to belong to a collegia.

**Please note: this "assemblage" was created solely for educational purposes. While the cremation urn KM 2903 and its contents may reflect an actual burial (it was purchased in the 1920's in Puteoli, Italy), the other objects in this "assemblage" (inscription, columbarium, and melted glass) do not come from the same archaeological context. A full explanation of this class project is found on the introductory page for this website. -

-

Permalink Reply by Slaying Crow O'Hagan on April 14, 2011 at 1:19

Permalink Reply by Slaying Crow O'Hagan on April 14, 2011 at 1:19 -

Death In Roman Society

Death In Roman Society

There was a range of views concerning the existence of an afterlife in Ancient Rome, as well as concerning what it was like. Such feelings often went with the time period, and are reflected, for example, in a major shift from cremation to inhumation (burial) as the chief method of burial around the 3rd century, possibly reflecting a heightened belief in the afterlife as a result of Oriental cults and Neoplatonism, or simply a desire to build gaudy burial monuments associated with some inhumations.

There was no generally accepted view of the afterlife, but many felt that the dead, living in their tombs, could influence the fortunes of the living in vague, undefined ways. Therefore, just to be safe, gifts and offerings were made to the deceased, and celebrations were held at tombs. There was a wide range of superstitious practice associated with burial. Evidence has been found of tombs being weighted down and bodies being decapitated for the purpose of preventing them from haunting the world of the living. Souls were thought to go the underworld (not Heaven or Hell) unless denied entrance by the gods and being forced to wander in limbo for eternity.

Funerals were generally organized by professional undertakers who provided mourning women, musicians, and sometimes dancers and mimes. For the poor, funerals were usually simple, but for the wealthy and especially the illustrious, the funeral was fantastic. Marked a procession through the streets of Rome, mourners paused in front of the forum for a ceremony of laudatio, where the deceased was displayed, normally upright, and a eulogy was read (the laudatio funebris). During the republic and earlier empire part of the procession was made up of the deceased's family, all wearing masks of his ancestors. Those wearing masks rode in chariots as a prominent part of the procession. This right, however, was restricted to those families who had held curule magistracies. The procession continued outside the city to the site of the burial or cremation.

Romans either buried (inhumation) or cremated their dead. Cremation had replaced inhumation as the chief burial rite until about the mid 3rd century, when inhumation took over again. Burials took place outside of towns, often roads, except in the case of young children. They were buried near their houses.

If cremation was the preferred method, the dead was cremated on a pyre, either at a special part of the cemetery (ustrinum) or at their already-dug grave, the bustum. Gifts and personal belongings were also often burned with the dead, after which the ashes were placed in some sort of container (an urn, a cloth bag, a gold casket, marble chest, some sort of pottery, glass, or metal). Jews and Christian objected to cremation, which died out in the fifth century.

In the case of inhumation, bodies were somehow protected, whether by a sack or shroud for the poor or by a wood, lead, stone, or otherwise manufactured coffin for the wealthy. Embalming bodies with gypsum plaster was also a common practice. Christian burials were usually oriented east-west.

Many graves were marked by tombstones, although these varied enormously. Many of them had inscriptions, while many more were marked with wood and quickly degenerated. Tombs of various shapes and sizes have been found, some containing the remains of several deceased. Some Romans also constructed hug mausoleums for themselves, such as the emperor Hadrian and the pyramid shaped tomb of Cestius.

Sometimes, although not often, the deceased seemed to have been granted a sort of "hero" status, almost being treated like a god after death. The deceased would occupy a temple, tomb, or mausoleum where the public could enter - seemingly a forerunning tradition to the Christian beliefs in the powers and sanctity of martyr's tombs.

Rock-cut tombs and catacombs have been found in Rome, Sicily, Malta, and North Africa.

Roman funeral clubs often deposited cremated remains in a collective tomb, called a columbarium, or "dove cote," each urn receiving a respective nidus, or "pigeon hole."

Pagan burials often included goods which might come in handy in the afterlife. The type of good was generally dependent on the wealth of the deceased's family. For the rich, vessels of food and drink, a gold ring, and various perfumes, such as frankincense and myrrh, could all be buried with the departed. A great number of burials have a gold coin in the mouth, the legendary fee of the underworld ferryman Charon. Other burial goods which have been found include boots, shoes, and lamps. It is thought these items were meant to help the departed on his or her journey through the underworld. -

© 2015 Created by Steve Paine.